Be Specific: What Animation Can Teach Us About Writing

|

|

Time to read 12 min

|

|

Time to read 12 min

I am a catastrophically huge fan of animation. From growing up watching Ghibli films to diving headfirst and frantically into the wider world of anime when I started college (beginning with the perfect-in-every-way Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood), I’ve found more stories that inspire me in anime than any other form of media (with fantasy literature being a close second). For as long as I can remember I’ve wanted to write stories that make readers feel the way I feel when I watch Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away, and a whole slew of other anime features—a desire that led to me studying those films through the lens of a writer, trying to figure out just what I could learn from them that would improve my own writing.

The biggest takeaway I gained from that study? How to write specific, vivid descriptions and details that accomplish multiple things at once.

Animation is a visual form of storytelling—not a purely visual form, as the soundscapes of films are key, but, by and large, animation uses visual cues for storytelling. It can’t “tell” its audience things the way books can; it has to “show” everything, from character personalities to setting to plot details—and it has to do so without becoming twenty hours long.

Which leads me to several storytelling lessons I pulled from animation:

For example, here is a set of gifs from the movie The Boy and the Beast (which I highly recommend):

Within these two frames, we’re given a setting that communicates the mood—night, the nearest light source is down the street (giving the scene a dark, moody feel), they’re in an area with a chain link fence around it, which rattles when the girl backs into it (tactile detail that heightens the intensity of what’s going on), rattles again when the boy slams his hands into it (same sound but different circumstances, an echo of previous anger that can now be seen as a side effect of compassion as the girl pulls him close/against the fence). And we have visual depictions of the characters’ tension—the boy is angry (which we can see by his expression, the way he moves, the way the girl backs away from and shouts at him, the rigidness of his arms going back and slamming down), the girl is frightened and concerned (which we can see by the way she flinches and holds her bag closer to her chest when the boy comes at her, the look she gives him after she slaps him), and the relationship between the characters (she hits him, but when he starts to drift back as if he’s going to fall, she reaches out and catches him, pulling him into her shoulder—she’s upset and he’s losing his temper, but they’re friends/these two aren’t strangers, and the girl isn’t in any real danger). All the little, visual details included in these frames tell us loads about the emotions of the scene, and what emotions the animators are trying to evoke in their viewers/convey with their characters and setting—and all that is accomplished through purely visual means.

The same can be accomplished through written descriptions—by utilizing salient, specific details that serve to paint a picture in the minds of our readers, we as writers can point them toward how we want them to picture or digest the scene we’re presenting them. If I was trying to write the above gifs as a scene, to convey the emotions going on, instead of saying “he was angry, she was frightened,” I’d mention the sound made by the fence when she backs into it too quickly, the way her eyes squeeze shut when she ducks her head down, how far back his arms swing when he’s about to slam his palms into the fence, the way she drops her school bag after slapping him, wanting to use both hands to grab ahold of him and stop him from stumbling back from her, how her back and his head hurt when they once more fall back against the fence. By being specific and deliberate in the details we include in our writing, we as writers can convey emotion in visual ways, and, at the same time, do our best to guarantee that readers interpret and understand the scenes and characters in our books the way we want them to.

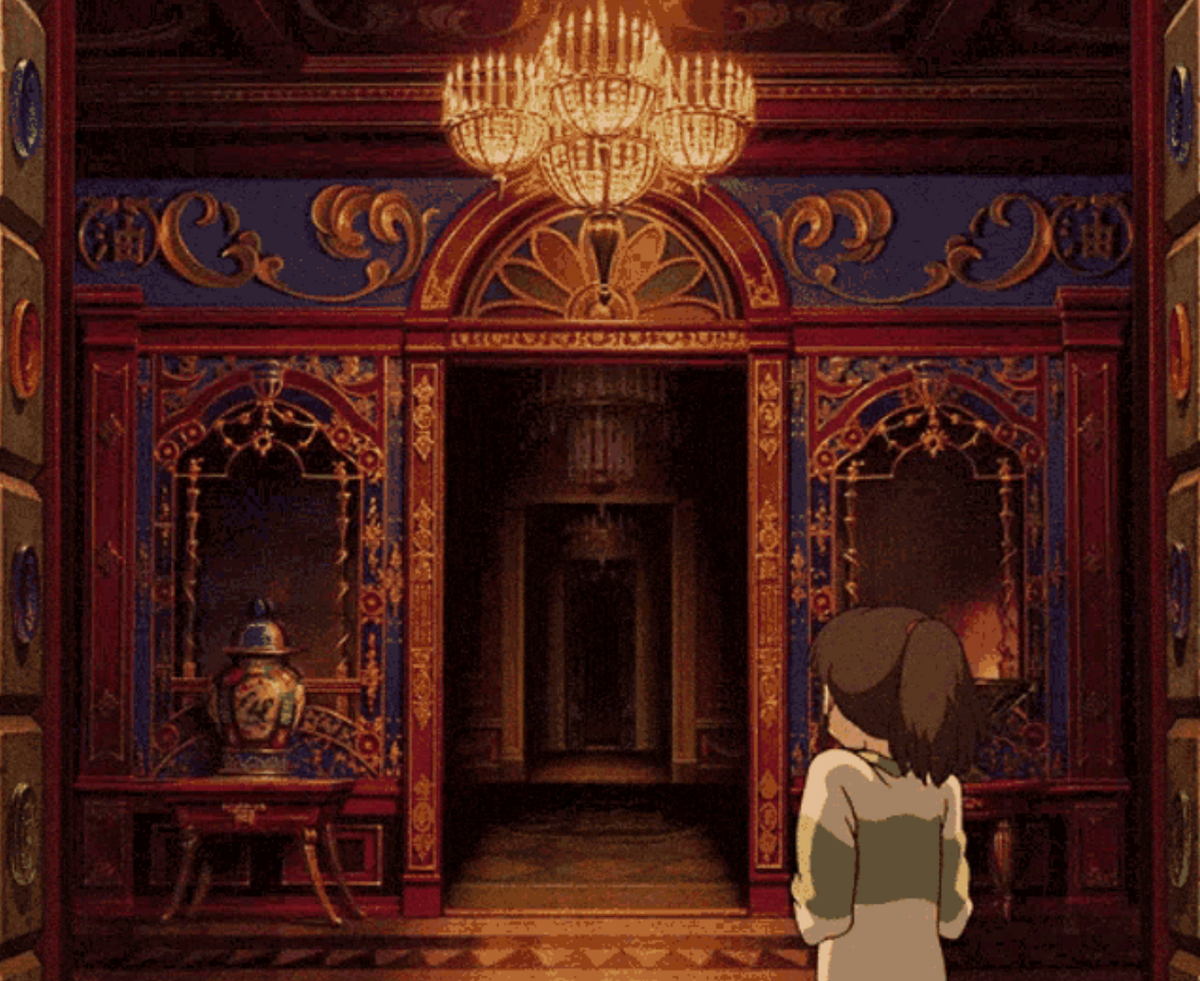

Specific, deliberate details can also go a long way in establishing and adding depth to our characters. I’ll give an example of that with a case study of the main character from Spirited Away, Chihiro:

What do these frames tell us about Chihiro? To me, the way her shoulders hunch when the doors open in front of her shows her timidity. The way she shouts and scowls, but is spooked by the wind, shows her age and immaturity. The way she focuses on cleaning her face from paper before anything else makes her relatable, while her frantic, almost dancing movements show just how freaked out she is. The way she ties her sash with that determined look on her face—using only one hand at first, then two, and without any hesitation—speaks of her growing confidence and fearlessness, contrasting starkly with the way she flinched at the sight of an opening door in that first gif.

It's these little moments that make characters and stories come to life—with unique, succinct details, you can characterize through every action, every movement, every flip of the wrist, roll of the eye, or careful folding of a napkin.

How do your characters eat? Jerking their head when they chew, slurping, with their hands or with their utensils? What do their actions while eating tell your readers about them? That they’re prim and proper, sloppy, so hungry they don’t care about appearances?

How do they run? Head down, head up, arms raised, without looking where they’re going, focused on the goal ahead of them?

How do they laugh, cry, show joy and displeasure? When they press their face into a washcloth, do they move their hands up and down to wipe their face, or do they move their face across the cloth while their hands stay still? How do they sit when they’re relaxed, when they’re frustrated, when they’re bored? When they trip, do they notice the pain in their foot, or the pain in their hands and knees when they fall?

In every situation and scenario, being specific in how you describe character actions and sensations—and making how each character reacts to every situation and performs every action unique—can brighten and sharpen your scenes, feeding information about who your characters are to your readers via those characters inherent, sometimes unconscious, decisions on how they move about and react to life.

I want to share a clip from the movie A Silent Voice that does what I’ve been talking about particularly well. Pay attention to the specific details focused on throughout this clip, and how those details contribute to the mounting tension, while also telling the viewer who these characters are, how they’re feeling, etc.

PLEASE NOTE: Trigger warning—attempted suicide. Do not click the following link if the content could potentially be harmful for your mental health.

I could honestly go on and on about this clip. How, even though he’s alarmed by what his friend is doing, Shoya takes the time to put the camera down and remove his shoes before coming inside. The way we zoom in on the sleeve of Shoko’s yukata and hair, waving in the wind and framed by the flaring lights of distant fireworks, the camera blurring and tilting as if we’re seeing from Shoya’s perspective, his vision slanting as he realizes what’s happening. How Shoya starts to panic and runs without looking where he’s going, the camera zooming in on his side hitting the chair with a painful impact that sends him sprawling, shouting as he goes. The moment he takes after he falls to cringe and clutch at his side, the pain distracting him for a moment he can’t really spare. How the window curtain flaps out, hiding Shoko from us and showing, when it falls back down, that she’s gone. The scrape of the front of his shoe against the railing as he tries to find purchase while struggling to hold onto her. The bead of sweat that falls from the side of Shoya’s face, dropping down to the river below as he tries to pull her up.

And I’ll stop there, because I’m already waxing overly poetic—my point here is that every moment in this scene, every detail the animators chose to highlight and include, shows us what’s happening and how the characters are feeling. Everything is working toward heightening the emotions in the scene so viewers become invested to the point of gasping when Shoko climbs up onto the balcony wall, shouting in alarm when Shoya hits the chair and falls, hoping as he works to pull her back up onto the balcony that he won’t fail, and knowing—as we watch his arms strain, his feet kick for purchase—that he might.

The first time I showed this clip to a creative writing class (for the same reason I’m writing this post), everything was deathly quiet after it ended. Until someone murmured, “You can’t just show us this without any warning.” To me, that statement alone proves just how masterfully this scene was executed.

I’ll end with a few caveats—this whole post I’ve been extolling the use of specific, vivid descriptions in your writing, but it is possible to go too far with descriptive prose, which in turn could make your stories “purple” and overwritten. The level of detail you go into with your writing should be proportional to the intensity and importance of the scene you’re writing. For example, let’s say we have a character who has spent an entire book getting ready for a fight that will define their lives. The day of the battle comes, they get into the fray, the moment of truth arrives, and we get this:

“I slipped. My arch enemy attacked me. He missed. I stabbed him in the gut. The end.”

Pretty lackluster, right? Readers will be disappointed if a climactic scene comes and goes in a vague flash—unless going by in a vague flash is the best way to land a gut-punch, or make a point; there are always exceptions! Typically speaking, though, if you spend an entire book building up to a grand battle, and that battle ends in two, plain sentences, you’re going to have angry muttering and possible book-throwing on your hands.

In the same breath, you can go too far with details in scenes that could pass in a paragraph without causing issue to the story. Let’s say we have the same character I mentioned before, the one spending their book getting ready for a big battle. Near the beginning of the book, the character gets into a skirmish, a fight in which they obviously won’t be dying (far too early for that), and nothing of import really happens outside of their survival. And let’s say that relatively unimportant scene is written like this:

As the blade arched down towards my neck, catching light upon its lustrous metallic skin in an arc of illumination so pure as to be near a peal, a sound that rang in my ears without ringing through the oxygen that wheezed from my mouth down my throat in a purr to my lungs, whom inflated very well possibly for the last time while my jaw dropped with a creak of bony hinges that put me in mind of the graveyard shifts I worked back in my hometown when more attractive work was lacking, I slid back on my hands, my heels digging into the mud upon which I sat in (or more accurately, squelched in), a scream hitching in the back of my throat like a chicken bone that scraped and itched. Shadow passed across my face, cast by my assailant, a man so tall as to rival the size of the trees I climbed as a young boy, burly arms swinging the tool of my demise with a grace unbefitting their bulk while yellowed teeth gnashed in my direction through the bottom of a helmet that had been dented and torn around the neck guard. I smelled grit and sweat and grime all around me, inside of my nose, plugged as it was by the blood and tears of battle. I felt my arms wobble under me, my knees weaken, though little good it did them, for I was already upon the ground, already so vulnerable and not to be dropped into further vulnerability by my treacherous kneecaps. I heard all the usual things—my mother’s voice chiding me, my father’s laughter, my lover’s whisper, my best friend’s ironic joke that someday my ambitions would get me in a compromising position. Tears filled my eyes, and I regretted just about everything I had done in my entire life to lead me to this moment. Ah, sweet agony, sweet irony, for I to die at such a young and beautiful age. The blade was yet another inch closer to me. I could feel the wind stirred by its downward swing as something slightly more than a lick upon my forelock, like a puppy’s playful snuggle upon my face, but, oh, not so tender and dear, but, oh, so full of the potential of pain and edges soon to be sawed into my flesh, which really was so thin and weak, now that I had a moment to think upon its composition. Ah, ah, to die, to die now, like a toad in a pit of slime, no, not even a toad, a worm, a wormy worm-worm that had no arms or legs with which to flee, only a belly as filthy as the mud through which I might crawl to salvation, if I only had the intelligence left to crawl, to slither, to slink away, away—

The man plunging the sword towards me grunted. He paused. I saw his mouth contort and felt a kinship with that grimace, that sneer of mixed surprise and annoyance. With a creak, he fell upon the ground beside me, an axe protruding from the back of his helmet. Quite dead. And I still quite alive.

In some cases, the above level of detail will be appropriate—but, again, if this scene was something unimportant, something that didn’t need to take up much time or space in the story, and it went long and descriptive with no apparent purpose or point in sight, then we’ve gone too far with our descriptions.

(Editor's note: If you haven't, be sure to check out Lynn's debut novel, The Dollmakers. A haunting fantasy reminicent of Studio Gibili films, it demonstrates these principles masterfully. And, if you want to stay up to date on all things Lynn Buchanan, visit her website.)

None of the observations I’ve made throughout this post are particularly groundbreaking—my point here is to encourage you to articulate, to analyze how the creators of these films use visual choices to evoke emotions, or show something about their story and characters that they can’t say outright. By consciously taking note of those instances, I hope you find ways to do the same in your stories.

And, of course, I hope I’ve convinced all of you to go and watch more animation! Animation is an art form that has a lot to teach any storyteller—to help further hammer in that point, below are a few more clips from anime movies that I (a) feel can work as further examples of what I’ve been discussing, and (b) will introduce you to movies that are must-sees, in my humble opinion.

Good luck with your writing, and remember—be specific!

—Lynn

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fkxg8ter_8k&t=4s

Wolf Children Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ea3fxOZer9E&t=1s

In This Corner of the World Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AjnJ9I7bgpY

Miss Hokusai Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L08HNKv9AhM